Ancient ruins plus modern restaurants and lodgings offer the best of both worlds.

Hurtling past llamas and alpacas and sheep in a taxi 12,000 feet up in the Peruvian Andes, I caught a glimpse of the valley below. It was framed by towering mountains. Their slopes gleamed with every imaginable hue of green, from deep forest to eye-popping emerald. In the distance, icy peaks disappeared into misty clouds. On the valley floor, the muddy Urubamba River, a mere wisp, snaked past small towns.

Travelers associate this region mainly with Machu Picchu, the Incan citadel made famous by American explorer Hiram Bingham. Although the Yale University professor raved about the ruins he “discovered” with the help of local farmers in 1911, he also waxed rhapsodic about the scene now before me. “There is no valley in South America,” he mused in a 1913 National Geographic Magazine article, “that has such varied beauties and so many charms.”

That’s why, while I was headed to Machu Picchu, I was in no hurry to get there. Reaching the ruins from Cusco, the nearest big city, requires a few hours’ travel through the Sacred Valley of the Incas (pictured above), and I was determined to slow down and savor a few days here. There’s good reason to do so. Flanked by Cusco at one end and Machu Picchu at the other, the 60-mile-long valley once lay at the heart of the Incan empire, and archaeological sites dot the area.

The valley is also home to some compelling 21st-century developments. Two attention-grabbing restaurants opened here—one helmed by the Peruvian chef presiding over one of the world’s top-ranked restaurants and another cantilevered dizzyingly over the side of a mountain. New hotels keep popping up, and PeruRail (pictured above) has debuted a luxurious twist on its popular train service. I wanted to get a taste of the old and the new.

An Inca victory

After a two-hour descent into the valley from Cusco, the taxi arrived at Ollantaytambo, a mountainside Incan archaeological site adjacent to a 13th-century village. I met Luis, a local guide wearing Asics running shoes and a black North Face windbreaker. He led me around a grassy plain at the site’s base and recounted the historic 1537 battle that took place here. Hoping to crush an Inca rebellion and capture its leader, Manco Inca, about 100 Spanish conquistadores raided the valley and got their first glimpse of the Ollantaytambo fortress.

Pedro Pizarro, a horseman on the scene, wrote: “It was a horrifying sight, for the place . . . is very strong, with very high terraces and with very large and well-fortified stone walls.” Stones and arrows soon pelted Pizarro and company. Then, implementing a plan he’d devised earlier, Manco Inca ordered part of a river to be diverted through canals to flood the base of the mountain. Water quickly rose to the horses’ torsos and prompted the Spaniards to retreat to Cusco. That rare Inca military victory over the Spanish gives Ollantaytambo a certain luster.

I followed Luis up the mountainside, climbing hundreds of steps, while pausing often to catch my breath in the thin air at 9,160 feet. High on a cliff, we encountered six perfectly cut monoliths standing side by side—the unfinished Temple of the Sun.

“Look at it,” Luis said. “It’s incredible.” He was right. The massive stones towered over us and glowed in the sunlight. Luis pointed out ancient carvings etched into their facades. From here, I gazed out at agricultural fields, red rooftops, and lush mountains. I imagined the Inca warriors perched here on that day nearly 500 years ago, hurling stones down at their invaders as the fate of the Inca civilization hung in the balance.

We descended the steps and walked to Ollantaytambo village, passing a budget hotel and pizza joint advertising Wi-Fi. I asked Luis how life in the area had changed since he was a boy. He talked about new architectural styles, disappearing trout in the river, and the loss of traditions. “When I was younger, we practiced ayni, the traditional bartering system,” he said. “You help me, I help you. I give you potatoes. You give me corn. No money changed hands.” He sighed. “Almost nobody practices ayni anymore.”

While clearly nostalgic for a bygone era, Luis also seemed to enjoy being a guide. Development, of course, often has two sides. It can pave the way for more visitors, bigger hotels, and better-paying jobs—what we often call “progress.” But it can also bring traffic and pollution, and hasten the disappearance of ancient customs.

Elevated dining at Mil

On another day, a taxi carried me up a series of long switchbacks into the mountains, to the old Inca saltworks at Maras, which remain in use. I strolled among hundreds of shallow, spring-fed pools where evaporating water had left brilliant white salt baking in the sun. We drove on, stopping to watch a young Quechua woman take alpaca wool and create strands that would be dyed and woven into blankets, another centuries-old tradition that happily survives. Steps away from her, a couple of dozen squeaking guinea pigs known as cuy peered out from the Andean adobe equivalent of a Habitrail, awaiting their fate as a local delicacy.

It was just about lunchtime, but I had other plans. I was eager to try Mil, the new restaurant from Peruvian skateboarder-turned-chef Virgilio Martinez and his wife, chef Pia León. The only address noted on the restaurant’s website was “ascending 500 meters from the archaeological complex of Moray”—the vertically arrayed Inca crop circles that had famously served as the chef’s inspiration. We knew we were close, but we weren’t sure how close. As the taxi motored along gravel roads amid expansive grassy plateaus, I looked out at Andean peaks rising in the distance—some pushing 20,000 feet. Every so often, a local woman wearing a wide-brimmed hat and traditional skirt would appear, strolling down the road. Way up here, time seemed to slow, and I couldn’t shake the buzzy feeling that I was somehow traversing the roof of the world, or at least of South America.

Finally, we asked a man next to a gate if he knew of the restaurant’s whereabouts. He grinned, lifted the barrier, and pointed up the hill. As soon as I walked through the front door, I recognized Martinez from his star turn on Netflix’s Chef’s Table series. Waifish, with a five o’clock shadow, he greeted visitors alongside his sister, Malena, who spearheads the operation’s native-ingredient research arm.

Like his celebrated Lima restaurant, Central, which ranks sixth on the 2019 World’s 50 Best Restaurants list (started in 2002 by the British trade magazine Restaurant and based on a poll of industry experts), Mil offers a tasting menu organized by the altitudes at which ingredients grow. I was soon enjoying an eight-course meal that featured exquisitely wrought local corn varieties, tree tomatoes, Andean potatoes, black quinoa, and even alpaca. Between courses, Martinez shared some of the motivation behind the restaurant.

“Yes, I’m Peruvian—but I’m still a guy from the city,” he said. “I wanted to understand the Andean worldview and know what was happening here.” He recognizes he’s not unique in that pursuit: “Some of the local shamans say there’s a spiritual migration to the valley, similar to Tibet, and I think they’re right,” he said, citing the recent explosion of yoga centers as a pretty solid benchmark.

Before leaving Mil, I chatted with Francesco D’Angelo Piaggio, a young Peruvian anthropologist who was working with Martinez and local indigenous communities to source ingredients for the restaurant. He pointed out potatoes growing in the fields that slope down from Mil’s front door. “We decided to put a little ayni here,” he said, referring to the traditional bartering system that Luis had mentioned. Local farmers work the restaurant’s land, keeping half the crops (and, yes, earning a wage). It might not be the purest form of ayni, but it’s an inventive approach that honors an age-old practice.

Spirituality in Pisac

On my last evening in the valley, I took a taxi to Pisac. Famous for its own Inca ruins that once comprised a royal residence, the tiny town is ground zero for the spiritual migration Martinez mentioned.

I wandered into the Mullu Café, where fliers advertised meditation retreats, full moon parties, and hallucinogenic ayahuasca ceremonies to a largely dreadlocked clientele. I ordered a mango-pineapple smoothie, sat overlooking the town plaza, and chatted with a couple of guys eating nearby. They were doctors from Uruguay who’d come to experiment with medicinal psychedelics and bask in the Andean vibes. This was a decidedly modern scene, yet time seemed fungible here, because moments later, several dozen locals wearing traditional clothing marched through the plaza below, playing drums and pan flutes in a procession I could imagine happening centuries ago.

Afterward, I chatted with a young taxi driver. I wondered how locals felt about the influx of visitors. As if on cue, he told me his name was Fausto (yes, that would be Faust) and that he hoped more people would come. But the resulting bargain wasn’t just about increased work and income, in his view. “There’s also an exchange of cultures and customs,” he said. “I can teach you Quechua, and you can teach me English. Life is better.” Perhaps a new version of ayni, I thought.

Onward to Machu Picchu

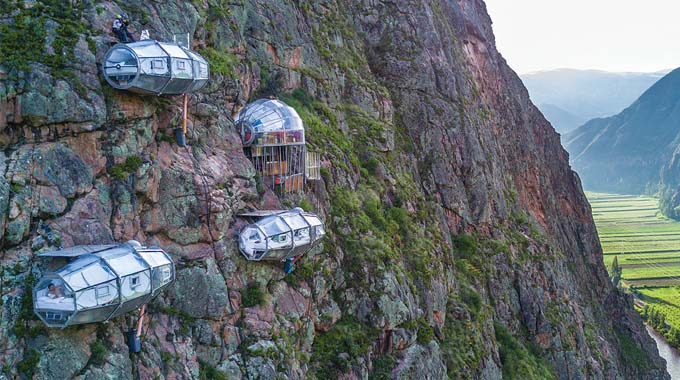

The time had come to leave for Machu Picchu. I boarded a PeruRail train (pictured above) in Urubamba for the three-hour trip that would include a three-course meal in a lavish dining car and drinks in the partially alfresco Observatory Bar Car. At one point, a conductor beckoned me to look skyward. Hanging 1,200 feet up, off the edge of a mountain, were several transparent, polycarbonate capsules—the newest of which was a restaurant that opened in 2017. The entire hospitality development, Skylodge Adventure Suites by Natura Vive (pictured below), looked as though it had been beamed here from the future.

As we rumbled onward, the valley became more lush and primordial. The river narrowed and churned, and I could feel the modern world receding. In the book I’d been reading, The Last Days of the Incas, Kim MacQuarrie writes that . . . “the ancient Incas once believed that history unfurled itself in a succession of ages.” According to MacQuarrie, many locals think that the next major epoch could be a return of the Inca world. It’s a beautiful idea. In fact, between visitors’ participation in ancient rituals and famed chefs celebrating centuries-old Inca cooking techniques, we might now be seeing the dawn of just such an age.

Jim Benning is a features editor at Westways.

* * * * *

Where to stay in Peru

In Cusco: Consider splurging for a luxurious, oxygen-enriched suite at Belmond Palacio Nazarenas, converted from a 17th-century convent. belmond.com. For alternative digs, try the comfortable El Mercado. elmercadocusco.com.

In the Sacred Valley: Settle in at the uber-tranquil Casa Andina Premium Valle Sagrado Hotel and Villas between Urubamba and Ollantaytambo. tinyurl.com/sacredvalleyhotel.

In Machu Picchu Village: Treat yourself to a night at Inkaterra Machu Picchu Pueblo Hotel, set on 12 acres in a lush cloud forest overlooking the Vilcanota River. inkaterra.com.

Getting to the Sacred Valley

By plane: Nonstop flights connect Lima and 11,152-foot-high Cusco. Due to the city’s elevation, many experts recommend descending immediately into the 9,500-foot-altitude Sacred Valley to acclimate before exploring Cusco at the end of your trip.

By train: PeruRail offers a range of options to and from Machu Picchu. The Sacred Valley train runs daily between Urubamba and Machu Picchu Village and includes a three-course meal served in a wood-paneled dining car. perurail.com.

Peru travel tip: Ask your doctor about combating altitude sickness with a prescription for Diamox (acetazolamide). Locals will tell you that drinking the coca tea offered gratis at most area hotels will also help ease symptoms.

Travel offers & deals